As Christian people trying to follow Jesus, and even more specific, as Christian ministry leaders trying to create spiritually forming environments for the families in our church, it’s easy to fixate on getting it right. I mean, our try-harder-to-be-better muscle is well-exercised. And it’s only a casual stroll from “excellence” to “perfection.”

I have two young-adult daughters—one in medical school and the other in grad school for occupational therapy. They are amazing and wonderful young women, with their share of the challenges that come with living in a broken world filtered through the normal impediments of their own brokenness. The other day I was talking with my wife about the “wins and losses” of our parenting—the ways we see our good impact strengthening our girls today, and the ways we see our bad impact creating hurdles for them. It’s so easy in these moments to slip into a false belief… That if we’d only been more, well, perfect, then our kids would have fewer issues to deal with.

This belief is false because it assumes that our agency in parenting, and in every area of our life, is the key that unlocks the door to wholeness and beauty. But the truth is that Jesus is far more shrewd than we give Him credit for. Like a martial artist, He takes the ugly we give Him and re-fashions it into something beautiful. He is not held back by our imperfections—of course, we still experience the existential consequences of our flaws, but anything given over to him is raw material for His artistry. We strive to do well, but our doing-well is not our backstop—in life or in ministry. Instead, our posture of yielded-ness in our relationship with Jesus essentially offers Him the raw material He needs to create art in our life, our parenting, and our ministry.

I was reminded of this truth after reading Roger Bretherton’s brilliant article “What Happens When Perfect Plans Are Outsmarted by the World?” in the online Christian journal Seen and Unseen. Bretherton, a clinical and coaching psychologist, recounts the extraordinary details surrounding one of the great live jazz performances in history. I’m a jazz nerd, and all jazz nerds know that Keith Jarrett’s recording of The Koln Concert is not only one of the bestselling jazz albums of all time, but also one of the most amazing examples of musical improvisation in history. Here’s a long excerpt from Bretheron’s article—it’s too good to give you snippets, so I’m inviting you into an extended section of his piece (please consider subscribing to Seen and Unseen as an “offering” of gratitude)…

This January marked the fiftieth year of a musical event so remarkable that a new dramatization of it premiered at the Berlin Film Festival to mark the occasion – the recording of The Köln Concert. (Watch the trailer of Köln 75.) If we are looking for a story of how beauty emerges from disaster, this one is worth telling. The event was organized by eighteen-year-old Vera Brandes, at that time the youngest concert promoter in Germany. She booked the Cologne Opera House, but given that it was a jazz concert, it was scheduled to begin at 11:30 p.m. following an opera performance earlier that evening.

The performer, jazz pianist, Keith Jarrett travelled to the concert from Zurich. But rather than flying, he sold his ticket for cash and opted to make the 350-mile trip north with his producer Manfred Eicher in a Renault 4. He had not slept well for several nights and arrived late afternoon in pain, wearing a back brace, only to discover that the opera house had messed up. The Bösendorfer 290 Imperial concert grand piano he had requested had been replaced by a much smaller Bösendorfer baby grand the staff had found backstage. The piano was intended for rehearsals only, in poor condition, out of tune, with broken keys and pedals. It was unplayable. Jarrett tried it briefly and refused to perform. But Vera Brandes had sold 1,400 tickets for the evening. So, while he headed out to eat, she promised to get him the piano he required.

But it was not to be. The piano tuner who arrived to fix the baby grand tells her a replacement is impossible. It was January in Northern Germany, the weather was wet and cold, and any grand piano transported in those conditions without specialist equipment would be damaged irreparably. They had to stick with the piano they had. Keith Jarrett’s meal didn’t go well either. There was a mix-up at the restaurant and their food arrived late. They barely had chance to eat anything before returning to the venue. And when Jarratt saw the tiny defective Bösendorfer still on the stage, he again refused to play, only changing his mind because Eicher’s sound-engineers were set up to record.

So the concert begins. A reluctant pianist—tired, hungry and in pain— sits at a ruined piano, and records the bestselling piano solo album and bestselling jazz album. Ever. He improvises for over an hour. Starting tentatively, exploring the contours, befriending the limitations of his damaged instrument—learning its capabilities as he plays. But soon Jarrett is whooping, yelling and humming with delight as he extracts beauty from the brokenness. The limited register forces him to play differently. The disconnected pedals become percussion. By the time he reaches the encore, the joy of his playing is irrepressible—it sends shivers down the spine. And when he finishes, the applause goes on. Forever.

Jarrett pulled off an impossible feat and sealed his reputation as one of the greatest pianists of his generation. And I take heart from the event, because when I face the world, I sometimes imagine I feel like he did facing that piano. Tired and pained and doubtful any good will come of playing. Can I order a new world, please? One more to my liking. One less likely to hurt. Yet I can’t quite shake off the intuition that there may be delight hiding in the doom, a treasure only unearthed by those willing to play.

The takeaway? Well, if we are “tired and pained and doubtful any good will come of [our ministry], maybe you and I can receive this story as a prompt from the Spirit—a nudge to maintain our “willingness to play.” Jesus told us the Kingdom of God belongs to children, so let’s reawaken our determination to relax and play, offering our own transcendent improvisations, though we’re playing with a broken-down “instrument.”

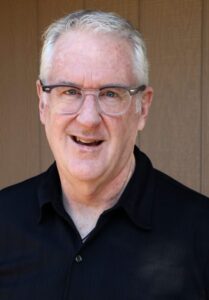

Rick Lawrence is Executive Director of Vibrant Faith—he created the new curriculum Following Jesus. He’s editor of the Jesus-Centered Bible and author of 40 books, including his new release Editing Jesus: Confronting the Distorted Faith of the American Church, The Suicide Solution, The Jesus-Centered Life and Jesus-Centered Daily. He hosts the podcast Paying Ridiculous Attention to Jesus.